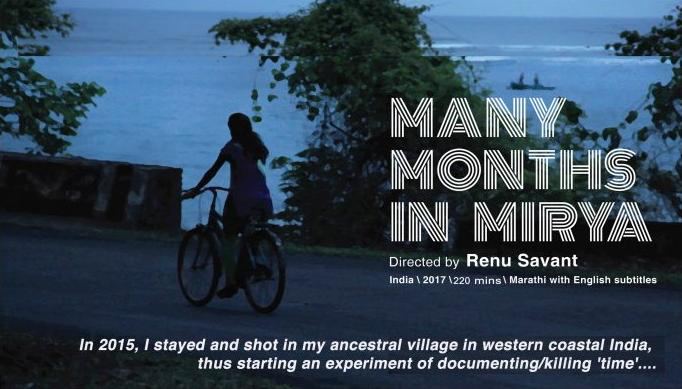

Renu Savant is a filmmaker and writer based in Mumbai. She is a graduate of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune. She has worked as a journalist and researcher in Mumbai. While studying at the FTII, in 2012 she received the Special Mention as Director in the 59th National Film Awards for her short film Airawat; and received the Swarna Kamal (the Golden Lotus) for Best Direction in the 62nd National Film Awards in 2015 for her short film Aaranyak. Apart from the National Film awards Renu won recognition through Special Jury Mention at the IDSFFK (2012), a student award at the Pune International Film Festival (2012), Best Short Film award at the 3rd Student National Awards (2015), and Best Short Film the at 3rd Eye Asian Film Festival (2016). After film school graduation, following her own expression, Renu made essay films and documentaries. She received the Early Career Fellowship from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, School for Media and Cultural Studies, in 2014 enabling her to produce a four-hour video documentary chronicle, Many Months In Mirya. The film received the John Abraham National Award for Best Documentary (India) in 2017.The film was one of the works exhibited at the Yokohama Triennale 2020, curated by Raqs Media Collective. In 2020 Renu was selected as a BAFTA Breakthrough India Honouree by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts for the year 2020-21. With the India Foundation for the Arts, Bangalore’s Arts Practice Grant between 2021-23, she created the film document “The Orchard and the Pardes”. This work is on the presence and conditions of work of seasonal immigrant laborers in and around Ratnagiri city and is part of her series of films set in the Konkan coast of Maharashtra. Mirya is Renu’s ancestral village in the Konkan region and she has worked there shooting for two previous films – Many Months in Mirya mentioned above and The Ebb Tide, a documentary commissioned by PSBT, New Delhi, and Doordarshan (the National Broadcaster), on small-scale fishing practices in the Mirya village creek. Renu’s works are film chronicles more than documentary films – as an unfolding record of the time and the people in the Konkan region. Renu’s work as a contemporary artist has been recognized through her participation in the Yokohama Triennale 2020, and it is her ‘impulse to capture the time’ of a place and people while exploring non-representational form that has given her valence in the discourse of contemporary art beyond documentary filmmaking. Renu highlights the specificities of the rural setting with its moral codes – both as psycho-geography as well as topography – that exert influence on the way gendered, migrant, and ‘outsider’ bodies are disciplined. Power structures are embedded in the very land of the rural region. In 1957, the erstwhile Mahar caste in Maharashtra converted en-masse to Buddhism under the leadership of Dr Ambedkar’s son. And yet all over the country, villages still have different castes communities living separately from each other. Renu acknowledges her power as an urban filmmaker who wants to record the rural space. There is a need for sensitivity in holding such power. Renu also wants to highlight the project as a ‘document of a woman filmmaker’. Many Months in Mirya was her first major work. Primarily in the tradition of a diary film, it experiments with long duration and chronicling through video as a political idea. The anonymous yet participative filmmaker becomes a witness to a certain duration in a certain place. Through the stories of various characters in the village of Mirya, the film reveals a microcosm of the country’s underbelly – its villages. The Orchard and the Pardes is about the male workforce as seen through the lens of a woman filmmaker. In this film, Renu’s project focuses on rural migration, which is relatively less looked at. Rural places are hotbeds of prejudice and fortresses of the landed powerful. “While cities offer anonymity, engagement, and more opportunity, rural areas are more claustrophobic places in many ways.”

RedCut: Tell us about your childhood and adolescence and how you decided to become a filmmaker. What factors supported and helped you on this path?

RS: At the age of 3 years, I was diagnosed with arrhythmia and implanted with a pacemaker at 6. I believe this fragility of the body – my body, has had a big impact on my mind. I spent long periods in the hospital till the age of 14 due to infections. Hence mortality, insecurity of life, and illness have been an ingrained part of my growing up. My experiences with hospitals, pain, and illness as a child were different from my peers’ childhoods. While other children were celebrating birthdays and picnics I was often lying in bed in a hospital, completely alone as I was in the intensive cardiac care unit with limited visiting hours. This has made me keenly aware of the position of the ‘outsider’. I grew up reading and stories were my world for a very long time. In adolescence, I read a lot of autobiographies including those of Indian political thinkers. Hence my empathy for the “outsider” figure came to be combined with a political and social awareness of what constitutes a lack of power in people. Furthermore, Indian society’s emphasis on communal conformity made me question many of the assumptions and rules behind gender and social roles, religion, caste roles, etc. This led to a questioning of my social position and this questioning continues for me even now. Stories continued to enthrall me as I got deeper into English literature through a Master’s at University and found my way to film school. Before this, I worked as a journalist and a researcher in Mumbai. At the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, with the camera I could tell more complex, personal stories intertwined with the impersonal, historical, and political. Since 2014 I have engaged with life in the rural Konkan as a woman filmmaker via the camera and filmmaking. I have understood that women have a secondary place in the soil I am standing on. I also understand that most of India lives in villages and small towns. This, combined with the increasing corporate-feudal and right-wing atmosphere has made it even more difficult to be themselves, for anyone who does not fall into the position of the majority religion, patriarchal male.

RedCut: As a female filmmaker, what obstacles have you faced in a patriarchal and male-dominated society, and how much impact do you believe your camera has had in advancing feminist goals?

Renu Savant

RS: The pressure to conform to given roles is immense on women in my society. Generally middle-class women are brought up with the constant insistence on docility and pleasing behavior. In this situation even having a different experience of life due to illness was so hard in terms of fitting in that I grew up constantly doubting myself. It has taken a lot of will to survive and expressiveness to keep making films and writing. But I believe this self-doubt has helped me in my creative work and questioning myself. My practice of documentation/chronicling through films is self-reflexive, not just due to my participatory (albeit ‘absent’) presence in the film. When I shoot, I am a participant in the situation but through my shooting of it. My interaction is very much felt by the people involved in a scene as I shoot by myself. In rural regions or in fact, in most places, a single woman with a camera is likely to be noticed in a certain way. Hence people respond to me through the camera – simultaneously performing themselves. My shooting often leads to a particular kind of relationship between the subject and the frame created by me. When executed consciously, I call this an assertion of my presence and agency as a woman. The chemistry of obstacles and a will to express is interesting at times. While working in a rural region, I have been rebuked, resented for no apparent reason, teased, and treated suspiciously. While there are some good reasons for the urban-rural divide in India, and we as filmmakers need to be cognizant of the class divide between urban-rural, misogyny is an entire subject on its own. Even in urban places like Mumbai, being ogled while simply walking on the street is a common thing. The level of resistance from male crew members and people whose support is needed for a shoot is sometimes astounding. It has become something of a fashion in the corporate film industry to gloss over these differences of treatment towards men and women, perhaps in the interests of appearing non-controversial or ‘easy to work with’. In my practice, I saw that many people I shot within the rural Konkan were positively affected by simply the visual of a woman with a camera or a woman calling directorial shots with a small crew. While shooting with men who were immigrant workers, I had prolonged contact with the subjects of my film. I am in connection with most of the key people who have appeared in my films. During the film shooting and after it, I could see that dialogue on gender was affected due to class and caste distinctions. But while it was misogynistic at times, there was a more friendly footing that we could find. As long as no one was intending to harm me, I can still call it a dialogue and I feel it changed all of us within that dialogue. The many stratifications of Indian society mean that people like filmmakers and artists who step out of their given social boundaries to connect with people outside of them, have to understand the political, social, and economic dimensions of such an interaction. I feel this responsibility lies with us as filmmakers and artists to find out how to have a meaningful and aware exchange in the making of our work.

RedCut: How do you choose your subjects and how do you approach them? To what extent do you, as a filmmaker, intervene in controlling the story and narrative? Do you believe the camera should portray reality without judgment, or do you see it as a tool to express your own beliefs and interpretations, revealing the truth in your way as you uncover and explore the story in front of the camera?

RS: So far I have made diary films while being aware that my political inclination was going to mean that these films were also political. I start with myself as the subject. The process of shooting leads me to the other characters as it is not a scripted film. The film is about the time that I spend in a particular place. It also depends a lot on how people respond to me. In my films, I record the situation, rather than the individual because I believe in giving a certain respect to the privacy of a subject. Hence in my films, I usually do not look for, or try to “capture” any particular information or personal story. Because I shoot situations, whatever comes out of the interaction between me and the person I am interviewing, becomes part of the scene. The camera is a tool and hence I think it is always going to express the interpretation and beliefs of the person holding it, knowingly or unknowingly.

RedCut: One of your films, “Monographs” was conceived in response to the atmosphere of uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic. To take advantage of the growing ubiquity of the video essay form, the Asian Film Archive, Singapore, asked ten filmmakers to reflect on the moving image in the context of their region. Drawing upon histories and archives that are both personal and regional, these works revealed new vistas of inquiry – ruminations that evince the essayists’ connections to cinema – made more poignant by the fact that they were created during various states of isolation and solitude. Tell us more about it and how you find the subject.

RS: I made the film in collaboration with artist Kush Badhwar. We decided to work on an Indian meme circulating in pandemic times, featuring a popular actor whose nationalist public speech was given at the end of the film. In the meme, this speech was redubbed with an erstwhile pandemic-related appeal to people to stay at home during lockdown. We decided to look at this meme with its nationalistic fervor and the situation in India during the pandemic. I imagined that I was part of the crowd listening to the actor’s public speech during its shooting. I wrote the voiceover of this film from the point of view of the female protagonist listening to the actor during its shooting.

RedCut: “Many Months in Mirya” is a lyrical ethnography of a village in the Konkan region of Maharashtra. It is a steady exploration of many characters and forces in the village; natural and human-made, historical and present. The film evokes the practice of the diary film, at once observational and reflexive, and draws power from its twin strategies of frugal economy and long duration. Tell us more about this film.

RS: Due to some personal reasons I decided to migrate out of Mumbai to my ancestral village and stay there. It is a beautiful village called ‘Mirya’ beside the sea in a region called Konkan. At that time, I also received the Early Career Fellowship given by SMCS, TISS, Mumbai and as part of the fellowship, I made the film in this village called Many Months in Mirya. I was fairly isolated in the village and my time there seemed to become elastic. It was to record this very personal experience that I started the film by deciding to practice the basics of filmmaking. I did the camera work myself to explore ideas of duration, framing and shooting an ongoing situation. I knew the film would be about people but it wouldn’t be scripted. I knew my impulses would take me to the politics that I wanted to reveal in the village society. So the film developed in the months I spent there, shooting daily and keeping a video diary of my daily life. I have a love for narrative and I could feel that despite not planning, some patterns of storytelling were emerging in my shooting. For example, my framing of the place went on changing as I stayed there longer, the characters whom I interviewed would often talk about the things we talked about the last time, conversations would be picked up where they were left off, their concerns about the village, some event which happened in the village at the same time, etc. And so through my experience of time and their personal stories, a picture of the village began to grow. This is what the final film became, a record, a digital diary of the months spent in Mirya village by me.

Redcut: In the current circumstances where the power of art and cinema is in the hands of the capitalist system, how much sustainability do you think independent cinema and independent thought have?

RS: In my opinion networks of art and cinema and their circulation are in the hands of capitalist systems and hence the way they operate is closed and through a high level of personal connections. In countries like India, demographically it is people from the middle to upper middle classes (and also middle to upper castes) are the ones who can afford to enter into arts or art cinema. This is increasingly so as inequality is rising in India. This means already capitalist systems are working when someone enters the world of being an ‘artist’. I feel that the ability to work alone, and the ability to exist on the fringes and be ok with it are some of the ways that independent thought can survive in a real way. This is very hard and I don’t know if it can be managed for long. I also believe that entering the market with a keen awareness of its parameters and perhaps practicing rigor of craft and thought, is the way one can keep working with the ideas that are important to us.